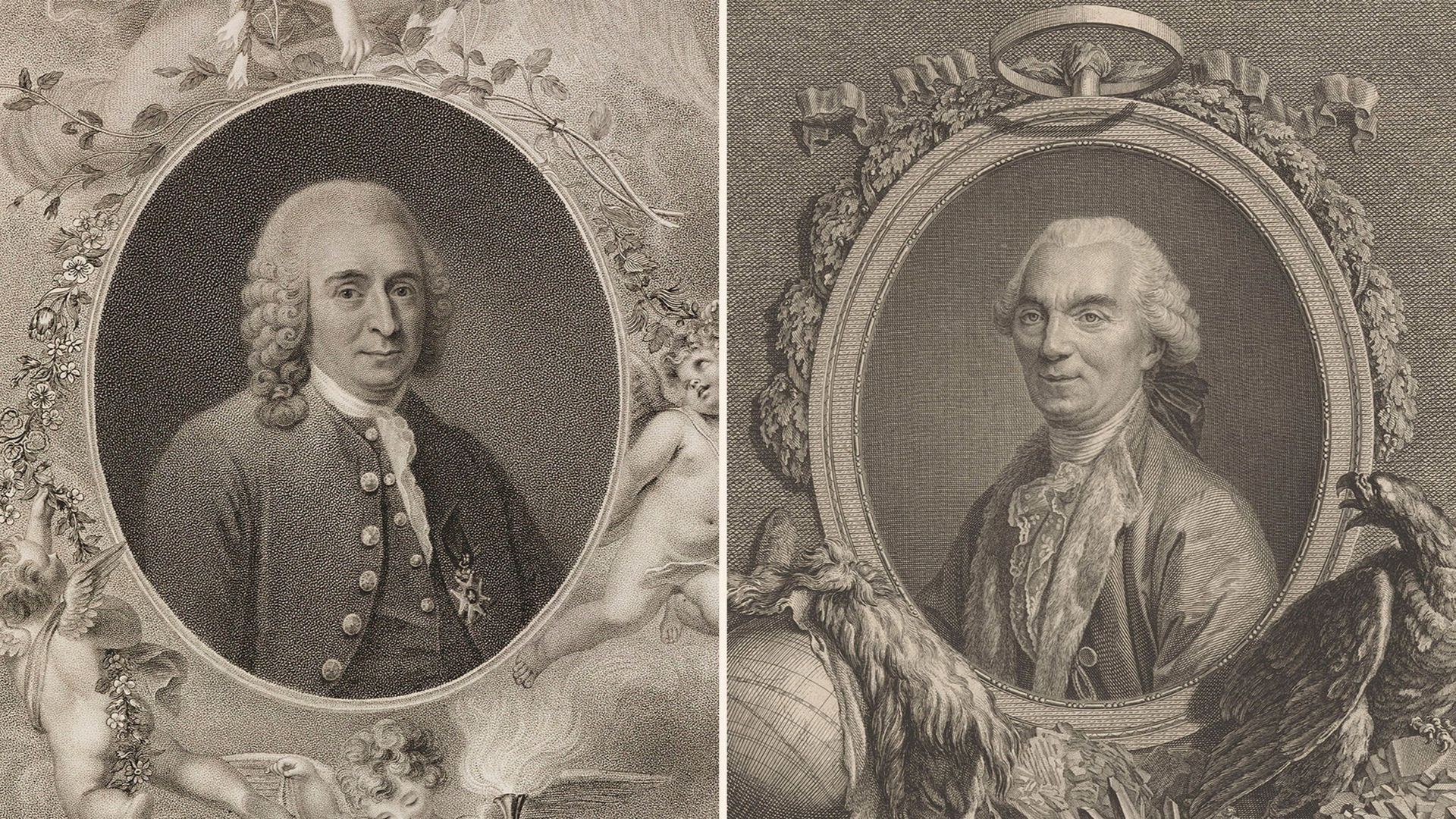

The aristocratic French polymath Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon chose a good year to die: 1788. Reflecting his status as a star of the Enlightenment and author of 35 popular volumes on natural history, Buffon’s funeral carriage drawn by 14 horses was watched by an estimated 20,000 mourners as it processed through Paris. A grateful Louis XVI had earlier erected a statue of a heroic Buffon in the Jardin du Roi, over which the naturalist had masterfully presided. “All nature bows to his genius,” the inscription read.

The next year the French Revolution erupted. As a symbol of the ancien regime, Buffon was denounced as an enemy of progress, his estates in Burgundy seized, and his son, known as the Buffonet, guillotined. In further insult to his memory, zealous revolutionaries marched through the king’s gardens (nowadays known as the Jardin des Plantes) with a bust of Buffon’s great rival, Carl Linnaeus. They hailed the Swedish scientific revolutionary as a true man of the people.